- A privacy program protects personal information, as well as trade secrets and other confidential information

- Identified individuals can be ascertained with certainty, while identifiable individuals can be indirectly identified through a combination of factors

- Whether information is “personal information” depends on how closely that information can be associated with a particular person—i.e., is the person “identified,” or merely “identifiable”

- Sensitive personal information is subject to greater regulation

- Personal information can be made into non-personal information through encryption, anonymization, or pseudonymization

- The source of information can also play a role in whether that data is subject to regulation

- Data Processing: Effectively anything that is done with personal information, including collection, storage, use, disclosure, transmission, and destruction

- Data Subject: The person whose data is being processed

- Data Controller: The organization that decides how information is processed

- Data Processor: The organization that processes information on behalf of the data controller; is limited in what it can do with the data by the data controller

CIPM

0%

Table of Contents

Welcome

I. Developing a Privacy Program

Introduction

Section A: Overview of a Privacy Program

0/4

1. What is Privacy Program Management?

a. What is Privacy?

b. What is a Privacy Program?

c. What is a Privacy Program Manager?

2. Key Privacy Management Concepts and Definitions

a. Identified and Identifiable Personal Information

b. Sensitive Personal Information

c. The Role of Encryption, Anonymization, and Pseudonymization

d. The Source of Information

e. Data Subjects, Controllers, and Processors

3. The Role of Accountability and Fair Information Practices

a. The Accountability Principle

b. Additional Principles Governing Privacy Management

i. Organizational Management

ii. Individual Rights

c. Examples of FIPs in International Frameworks

i. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines (1980)

ii. The Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Automatic Processing of Personal Data (1981)

iii. The Madrid Resolution (2009)

Section I.A Review

Section B: Implementing a Privacy Program at the Organizational Level

0/8

1. Leveraging the Entire Organization

2. Establishing Privacy Governance and Creating a Company Vision

a. Establishing Privacy Governance

b. Developing a Privacy Vision

c. Illustrative Examples

d. Obtaining Executive Approval

3. Data Governance Models

a. Centralized Model

b. Distributed Model (a/k/a Local Model or Decentralized Model)

c. Hybrid Model

d. Advantages and Disadvantages

e. Choosing a Model and the Location for the Privacy Function

4. Defining the Scope of a Privacy Program

a. Identifying the Personal Information Processed by an Organization

b. Identifying Applicable Privacy Laws and Regulations

c. Additional Considerations and Organizational Objectives

5. Developing a Privacy Strategy

a. Making the Business Case for Privacy and Data Protection

b. Identifying the Stakeholders

c. Interfacing With the Organization

d. Accountability Over the Process

e. Taking Privacy Out of the Abstract

i. Developing Data Governance Strategies

ii. Obtaining Funding and Privacy Budgets

iii. Maintaining Program Flexibility

6. Structuring a Privacy Team

a. Common Privacy Roles and Titles

b. The Growing Need for Privacy Expertise

c. Designated Privacy Leaders

d. Data Protection Officers (“DPO”) and the GDPR

i. When Must a DPO be Appointed?

ii. The Role of the DPO

e. Establishing the Professional Competency of Team Members

7. Communication and Awareness

Section I.B Review

Knowledge Review #1

II. Privacy Program Framework

Introduction

Section A: Developing a Privacy Program Framework

0/6

1. What is a Privacy Program Framework?

2. Risk and Compliance Frameworks

a. Legal Compliance Frameworks

b. Fair Information Practices

c. NIST Privacy Framework

3. Using Privacy Tech to Manage a Privacy Framework

4. Developing Organizational Privacy Policies, Standards, and Guidelines

a. The Privacy Policy Life Cycle

b. Key Components of a Privacy Policy

c. Rationalizing Privacy Requirements

d. Identifying Personal Data Collection Points

5. Defining Privacy Program Activities

a. Education and Awareness

b. Internal Policy Compliance

c. Data Inventories, Data Flows, and Data Classification Schema

d. Risk Assessments

e. Incident Response Process

f. Monitoring Regulatory Environment

g. Internal Audit and Risk Management

Section II.A Review

Section B: Implementing a Privacy Program Framework

0/9

1. Introduction

2. Communicating the Privacy Framework to Internal and External Stakeholders

a. Internal Communication

b. External Communication

3. Ensure Continuous Alignment With Applicable Laws and Regulations

4. The General Data Protection Regulation

a. Scope of the GDPR

b. Data Processing Principles and Lawfulness

c. Individual Rights

d. Organizational Obligations

e. Regulatory Powers

5. Other Global Privacy Laws

6. United States Privacy Laws

a. Federal Laws

b. State Data Security Laws

c. State Data Breach Notification Laws

d. California Consumer Privacy Act (“CCPA”) and the California Privacy Rights Act (“CPRA”)

i. The Scope of the CCPA

ii. Individual Data Subject Rights

iii. Controller Obligations

iv. California Privacy Protection Agency

v. Enforcement of the CCPA

e. Other Comprehensive Privacy Legislation

i. Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (“VCDPA”)

7. Self-Regulatory Authorities

8. Cross-Border Data Sharing

a. The Risks of International Data Transfers

a. The Surprise Minimization Rule

b. International Data Transfers Under the GDPR

i. Lawful Transfers

ii. Adequacy Decisions

iii. Appropriate Safeguards

iv. Derogations

v. The Implications of Schrems II and Transfer Impact Assessments

Section II.B Review

Section C: Using Privacy Metrics

0/5

1. Introduction

2. Identifying Your Intended Audience

3. Defining Privacy Metrics

a. Privacy Metric Development Template

b. Metric Owners

c. Identifying Data Sources for Privacy Metrics

4. Analyzing Privacy Metrics

a. Compliance Metrics

b. Trend Analysis

c. Privacy Program ROI

d. Business Resiliency Metrics

e. Privacy Program Maturity

f. Resource Utilization

g. IAPP’s DPO Report Template

Section II.C Review

Knowledge Review #2

III. Privacy Operational Life Cycle

Introduction

Section A: Assess Your Organization

0/7

1. Documenting a Baseline of Privacy Program Activities

2. Data Assessments

a. Data Inventory

b. Data Flow Maps

c. Data Classification

d. Developing Data Inventories, Maps, and Classification Schema

e. GDPR Records Processing Requirements

3. Risk Assessments

a. Privacy Assessments

b. Privacy Threshold Analysis and Privacy Impact Assessments

c. Data Protection Impact Assessments

i. When is a DPIA required?

ii. What must be included in a DPIA?

iii. Consultation With Supervisory Authorities

iv. Transfer Impact Assessments (TIAs) and Legitimate Interest Assessments (LIAs)

4. Assessing Data Processors and Third-Party Vendors

a. Choosing a Third-Party Vendor

b. Vendor Contracts

c. Cloud Computing Issues and Data Residency

i. Vetting Cloud Vendors

ii. Terms in Cloud Computing Contracts

iii. E.U. Cloud Code of Conduct

d. Restrictions on Third-Party Data Sharing

5. Physical Assessments

a. Physical and Environmental Aspects of Information Security

b. Assessing the Physical Environment

c. Bring Your Own Device and Data Loss Prevention

6. Mergers, Acquisitions, and Divestitures

a. Privacy Challenges of M&A Transactions

b. Completing Due Diligence

c. Managing the Transition

d. Creating Alignment Post-Integration

Section III.A Review

Section B: Protect Your Organization

0/13

1. Data Governance

a. What is Data Governance?

b. Data Life Cycle Management

c. Data Collection

d. Data Retention and Data Destruction Policies

e. Media Sanitization

2. Information Privacy vs. Information Security

a. Where Privacy and Security Diverge

b. Where Privacy and Security Overlap

c. Privacy as a Compliment to Information Security

3. Information Security Practices

a. The CIA Triad

b. Security Controls

i. Purpose of Controls: Preventative, Detective, and Corrective

ii. Types of controls: Physical, Administrative, and Technical

c. ISO Standards 27001 and 27002

4. Cybersecurity and Online Threats

a. Common Threats

b. Cybersecurity Threat Management

c. Threat Modeling

d. Intrusion Detection and Prevention

e. The Role of Human Error

5. Identifying Privacy Risk

a. Nissenbaum’s Contextual Integrity

b. Calo’s Harm Dimensions

c. Solove’s Taxonomy of Privacy

d. Factor Analysis of Information Risk (“FAIR”) Method

6. Access Management

a. Authentication

b. Authorization

c. Principle of Least-Privilege Required

d. Role-Based Access Control (RBAC)

e. Other Access Control Methods

7. Privacy by Design and by Default

a. The Seven Principles of PbD

b. Data Protection by Design and Default Under the GDPR

i. Scope

ii. Article 25(1) – Data Protection by Design

iii. Article 25(2) – Data Protection by Default

c. Privacy Design Strategies

d. ISO Privacy by Design Standards

8. Systems Development Life Cycle and Privacy Engineering

a. System Development Life Cycle (SDLC)

b. Plan-Driven vs. Agile Development

i. Waterfall Method

ii. Spiral Method

iii. Scrum Method

iv. DevOps Method

9. Aligning Privacy Policies Across the Organization

a. The Importance of Alignment

b. Communicating Across the Organization

c. Understanding the Costs and Tradeoffs

10. Organizational Measures: Effective Policies

a. Designing Effective Policies

b. Specific Policies That Impact Privacy

i. Acceptable Use Policies

ii. Information Security Policies

iii. Procurement Policies

iv. Human Resource Policies

v. Secondary Use Policies

11. Collaborating With Privacy Technologists

12. Privacy-Enhancing Technologies

a. Identification and De-Identification of Data

b. Anonymization Techniques

c. Aggregation and Differential Privacy

d. Encryption

i. What is Encryption?

ii. Symmetric vs. Asymmetric Encryption

iii. Hashing

Section III.B Review

Knowledge Review #3

Section C: Sustain the Privacy Program

0/5

1. Monitoring the Privacy Program

2. Auditing the Privacy Program

a. Types of Audits

b. The Audit Life Cycle

c. Creating Appropriate Audit Trails

d. Attestations and Self-Assessments

3. Training and Awareness

a. Training vs. Awareness

b. Training and Awareness as a Communication Tool

c. Training and Awareness as a Cost-Saving Mechanism

d. Building a Training and Awareness Program

4. Artificial Intelligence Governance

a. What is AI Governance?

b. The Privacy Challenges of AI

c. Other Risks of AI

d. Responsible AI

5. The Regulation of Artificial Intelligence

a. Application of Comprehensive Privacy Laws

b. E.U. Artificial Intelligence Regulation

i. Scope of the AI Act: Ai Systems, Providers, Deployers, and Extraterritorial Reach

ii. Categorization of Risk

iii. Accountability and Transparency Requirements

iv. General-Purpose AI Models

v. Enforcement and the European Artificial Intelligence Board

Section III.C Review

Section D: Respond: Data Subject Requests

0/8

1. Introduction

2. Privacy Notices

a. Legal Consequences of a Privacy Notice

b. Updating a Privacy Notice

c. Designing an Effective Privacy Notice

i. Common Elements

ii. Layered Notices

iii. Just-in-Time Notices

iv. Privacy Dashboards

v. Privacy Icons and Visualization Tools

vi. One or Multiple Privacy Notices?

3. Data Subject Consent

a. Methods of Obtaining Consent

b. Consent Under the GDPR

i. Freely Given

ii. Specific to the Processing

iii. Informed

iv. Unambiguous

c. Obtaining Consent From Children

d. Responding to a Withdrawal of Consent

4. Handling Data Subject Requests and Complaints

a. Centralized Processing

b. EDPB Guidance

i. Determining What Information Related to Requesting Data Subject

ii. The Modalities of a Response

5. Data Subject Rights: The GDPR

a. Right to be Informed

b. Right to Access and Information

c. Right to Rectification

d. Right to Erasure (“Right to be Forgotten”)

e. Right to Restrict Processing

f. Right to Data Portability

g. Right to Object to Processing

h. Right Not to Be Subject to Automated Decision-Making and Profiling

6. Data Subject Rights: U.S. Law

a. Federal Law

b. State Law

7. Additional Data Subject Rights Globally

a. Canada

b. Latin America

c. Asia

d. Australia and New Zealand

Section III.D Review

Section E: Respond: Privacy Incidents

0/8

1. The Costs of a Privacy Incident

2. Legal Compliance and Defining a "Data Breach"

3. Incident Response Planning

a. Developing a Plan

b. Training

c. Key Roles and Responsibilities

d. Insurance Coverage

e. Managing Vendors

4. Incident Detection

a. Coordination of Incident Detection

b. What to Look For

5. Incident Handling

a. Steps in an Incident Response

b. Leadership Response Team

c. Investigation of an Incident

i. Containment and Remediation

ii. Preserving Privilege

iii. Conducting an Incident Impact Assessment

d. Working With Insurers and Other Contracted Parties

e. Managing an Incident Register

6. Notification and Reporting a Data Breach

a. Internal Notifications and Progress Reporting

b. Notifying Affected Individuals

i. Letter Dropping Campaigns

ii. Call Center Campaigns

iii. Remediation Offers

c. Notification to Regulatory Authorities

7. Incident Follow-Up

Section III.E Review

Knowledge Review #4

Conclusion

Full Exam #1

Full Exam #2

Key Privacy Management Concepts and Definitions

A privacy program seeks to protect and manage multiple categories of information. Among other pieces of data, a privacy program may seek to protect trade secrets and other confidential or proprietary information about an organization. Most importantly, however, a privacy program governs an organization’s use of “personal information,” sometimes referred to as “personally identifiable information.”

a. Identified and Identifiable Personal Information

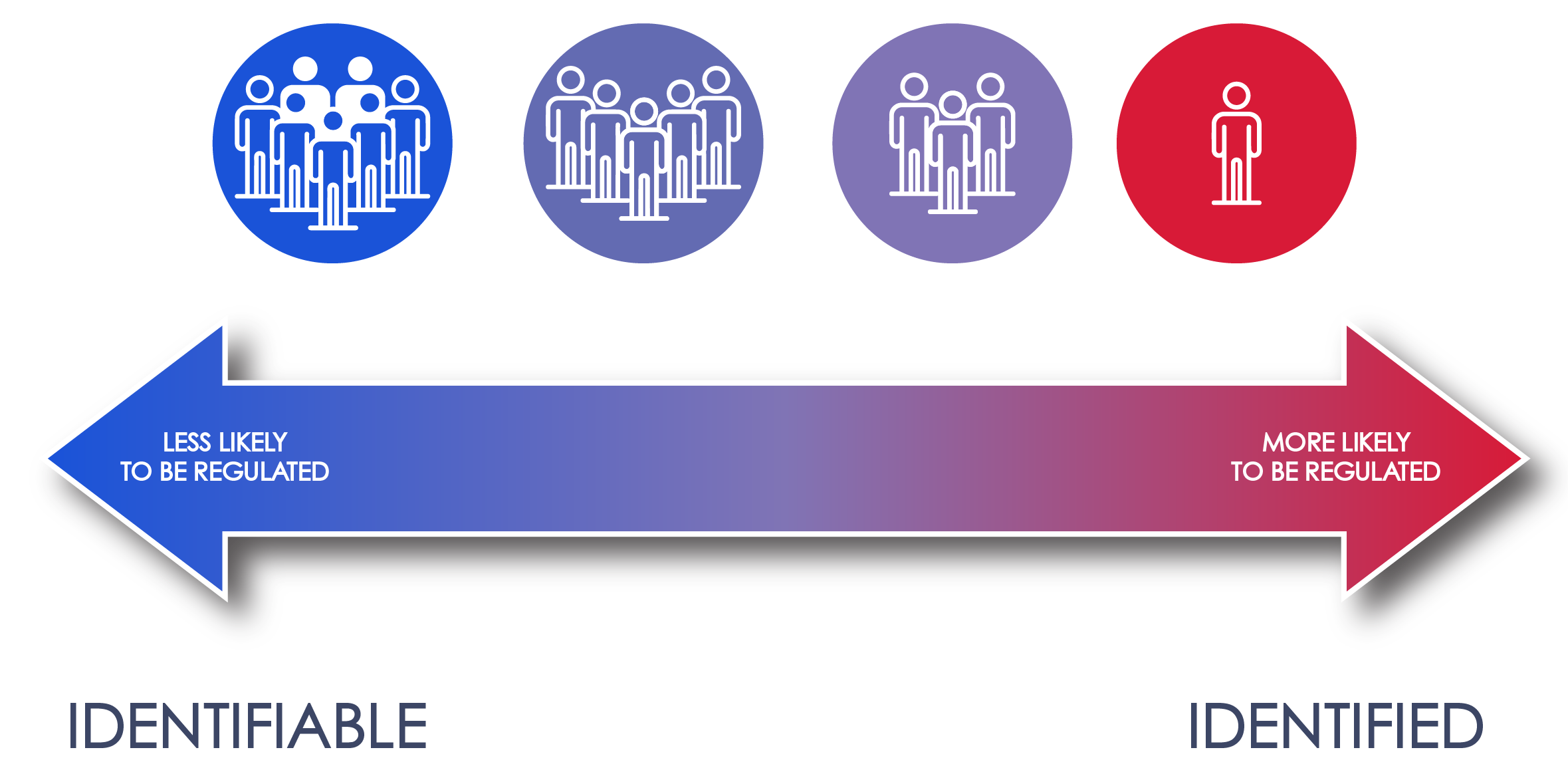

In some jurisdictions, such as the United States, laws may differentiate between information that makes an individual “identified” from information that makes a person “identifiable.”

An Identified Individual is one who can be ascertained with certainty—for example, by reference to a unique government-issued identification number.

An Identifiable Individual, on the other hand, is one that can be indirectly identified through a combination of various factors. As the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) defines it, “an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.”1

The difference between an identified individual and an identifiable individual is best thought of as a sliding scale; the more closely information is associated with a person, the more likely they are to be considered an identified individual. As an example, knowing that a person lives in a specific city would not make that person identified, as many others also live in any given city. Combine that city information with a street address and that combination will still likely not identify one specific person. That information could, after all, be associated with any member of the household. But, if you associate that street address with even more information, such as the height and sex of a person living at that address, it might (or still might not) be possible to identify someone with certainty. At the other extreme, information such as a social security number will identify a specific person without reference to any additional information.

Typically, a privacy program will govern an organization’s use of all “identifiable” personal information.

b. Sensitive Personal Information

There is a narrower category of personal information often referred to as “sensitive personal information.” Information falling into this category generally relates to data that is particularly sensitive for one reason or another. The GDPR, for example, specifically defines “special categories of personal data” to include information related to “racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, or trade union membership, and the processing of genetic data, biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person, data concerning health or data concerning a natural person’s sex life or sexual orientation. . . .” 2

Some laws place heightened protections over the use of sensitive data or seek only to regulate particularly sensitive data. Article 9 of the GDPR, for example, places restrictions on the processing of sensitive personal data, with only certain identified exceptions.3 A good example of this in the United States is the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (“HIPAA”), which only regulates access to personal health records; it does not regulate all personal information that might be maintained by a health facility. Similarly, under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (“FCRA”), tighter restrictions are placed on the disclosure of medical records than the restrictions applicable to other information contained in a “consumer report.”4 These are just two examples of many found throughout American law.

c. The Role of Encryption, Anonymization, and Pseudonymization

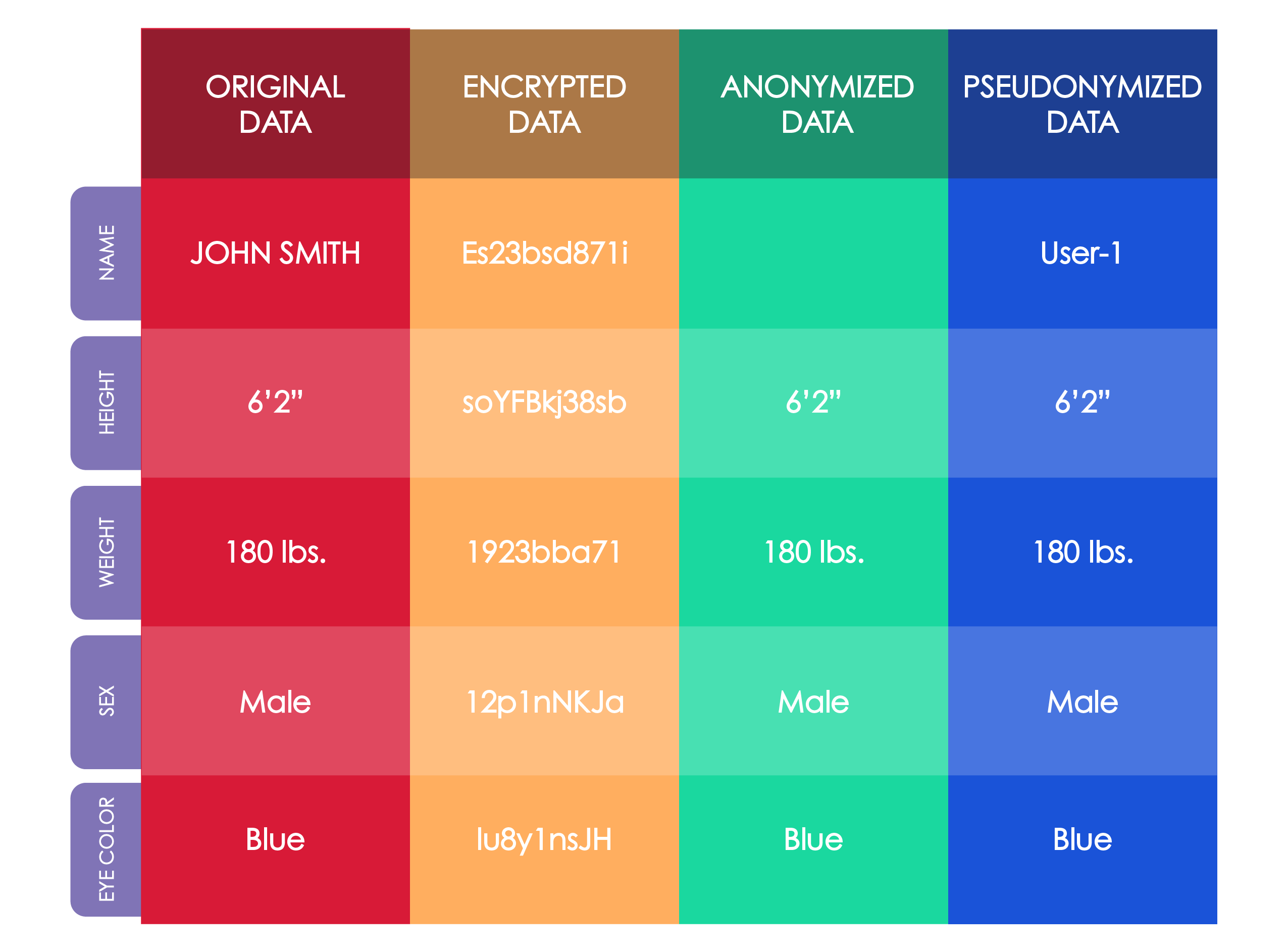

With rare exception, non-personal information is not subject to data and privacy protection laws. Importantly, under many laws and regulations, it may be possible to take data that would otherwise be considered personal information and turn it into non-personal information by de-identifying or anonymizing that data.

One way this occurs is through the Encryption of data, which is the process of taking data and putting it into an unrecognizable form.5 Anonymization, on the other hand, is a technique whereby data is stripped of its identifying information. A closely related technique is the “Pseudonymization” of data. This is the process through which information is associated with a pseudonym such that it can no longer be attributed to a specific person without the use of additional information.6 The benefit of pseudonymization compared to anonymization is that this process can be reversed so that the information can be re-identified with a specific person.

d. The Source of Information

In addition to the nature of the information at issue, it is also important to understand the source of information. Personal Information can be derived from any number of sources. These can include public records (e.g., court filings), publicly available information (e.g., publicly accessible social media accounts), and non-public information. The protection of personal information is focused most heavily on non-public information, but laws and regulations may sometimes affect information coming from publicly available sources, or even data from public sources. As an example, court rules often permit litigants to file certain types of information or documents under seal, even though that information would generally be considered public information.

e. Data Subjects, Controllers, and Processors

In discussing personal information, it is also helpful to define certain terms related to the processing of data. Many of these terms originated in Europe but have become somewhat standard terms used throughout the privacy and data security industries.

The term “processing,” or “data processing,” is a term that refers to almost anything that is done with personal information—everything from collection to storage to deletion. The GDPR, for example, expansively defines data processing as “any operation or set of operations which is performed on personal data or on sets of personal data, whether or not by automated means, such as collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, alignment or combination, restriction, erasure or destruction.”7

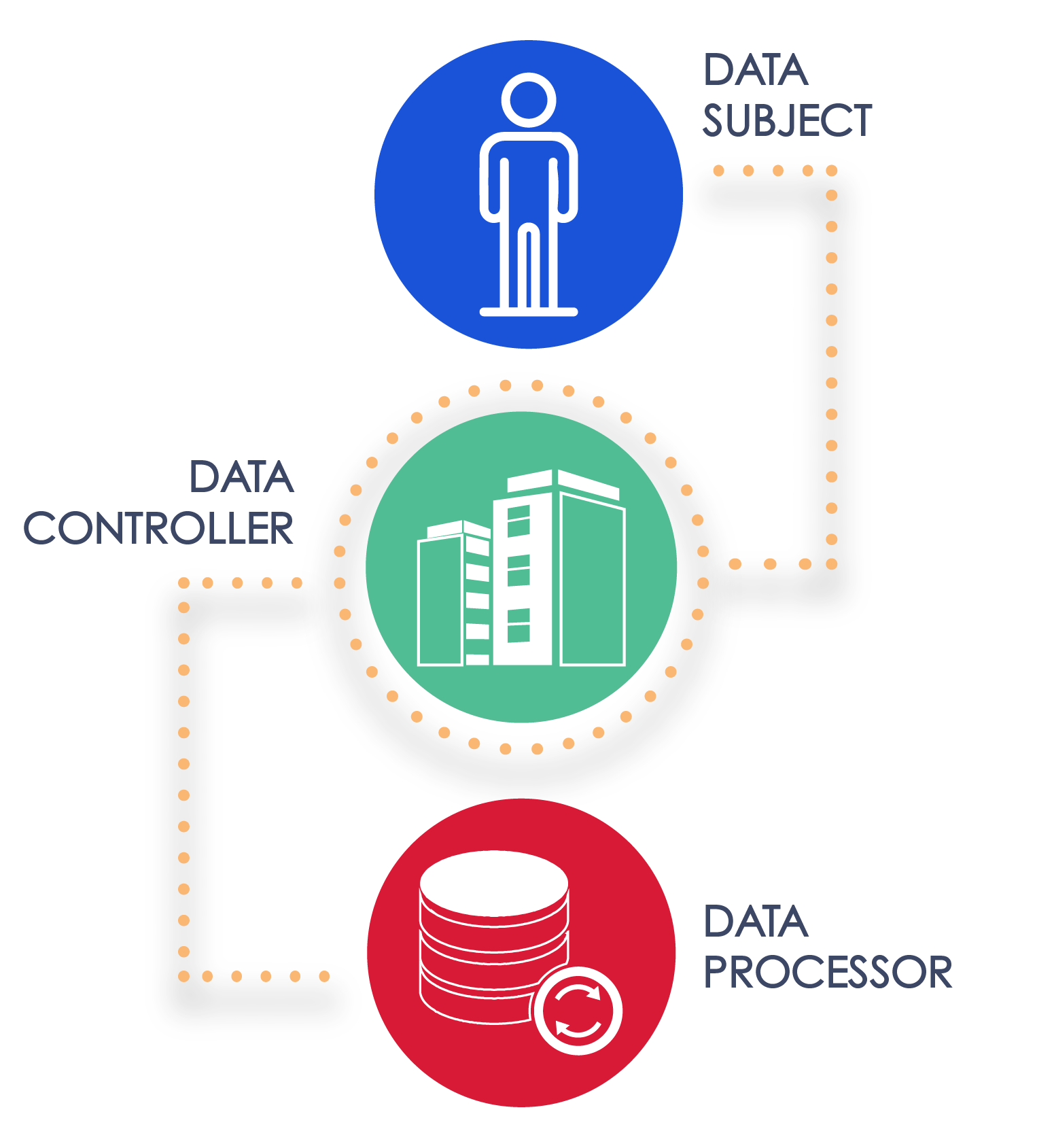

Three categories of persons are involved in processing personal information: a data subject, a data controller, and a data processor.

A Data Subject is the individual whose personal information is being processed.8

A Data Controller, on the other hand, is the organization (but it may also be an individual) that decides how personal information is being utilized and processed. As defined by the GDPR, a controller is “the natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body which, alone or jointly with others, determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data.”9 The organization that is the data controller is typically subject to the heaviest amount of regulation by privacy and data protection laws.

Lastly, the term Data Processor refers to any organization or person that processes data on behalf of a data controller.10 Under this definition, one organization may be both a data controller and a data processor, depending on what is processed and on behalf of whom. That is to say, one organization can be a data controller with respect to the processing of some data but a data processor with respect to the processing of other data.

Likewise, the term data processor also refers to all subsequent data processors down a chain of outsourcing. Accordingly, if a data processor processes certain types of data itself on behalf of the controller, but also contracts with a third-party to conduct further analysis on that data, both parties would be considered data processors. The second processor is sometimes called a “sub-processor.”

The main difference between a data controller and a data processor is who has ultimate authority over the data. A data processor is not permitted to do any processing beyond what the data controller permits or beyond what the data controller itself could do with that information. Because a data processor acts on behalf of the controller it necessarily serves the controller’s interest rather than its own interests.11 Even though a data controller is the party that has ultimate authority about how data is processed, both data controllers and data processors implement their own separate privacy programs.

Privacy professionals must be aware of the fact that the terms described above are only general terms and definitions. Numerous laws use different names to refer to these same concepts. In the United States, for example, a data processor is referred to as a “business associate” under HIPAA12 and as a “service provider” under the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act.13

Key Points

Sources

1. GDPR, OJ 2016 L 119/1, Art. 4(1).

2. GDPR, OJ 2016 L 119/1, Art. 9(1).

3. GDPR, OJ 2016 L 119/1, Art. 9.

4. 15 U.S.C. § 1681b(g).

5. Encryption, TechTerms, available at https://techterms.com/definition/encryption.

6. GDPR, OJ 2016 L 119/1, Art. 4(5).

7. GDPR, OJ 2016 L 119/1, Art. 4(2).

8. GDPR, OJ 2016 L 119/1, Art. 4(1) (defining “data subject” as a “an identified or identifiable natural person”).

9. GDPR, OJ 2016 L 119/1, Art. 4(7).

10. GDPR, OJ 2016 L 119/1, Art. 4(8).

11. European Data Protection Board, Guidelines 07/2020 on the Concepts of Controller and Processor in the GDPR at 26 (July 7, 2021), available at https://www.edpb.europa.eu/our-work-tools/our-documents/guidelines/guidelines-072020-concepts-controller-and-processor-gdpr_en.

12. 45 C.F.R. § 160.103.

13. 12 C.F.R. § 1024.31.