In the previous Section of this study guide, we answered the question of when the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) applies to the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by organizations. We turn now to PIPEDA’s substantive provisions.

Section 5(1) of PIPEDA states: “Subject to sections 6 to 9, every organization shall comply with the obligations set out in Schedule

1.”1

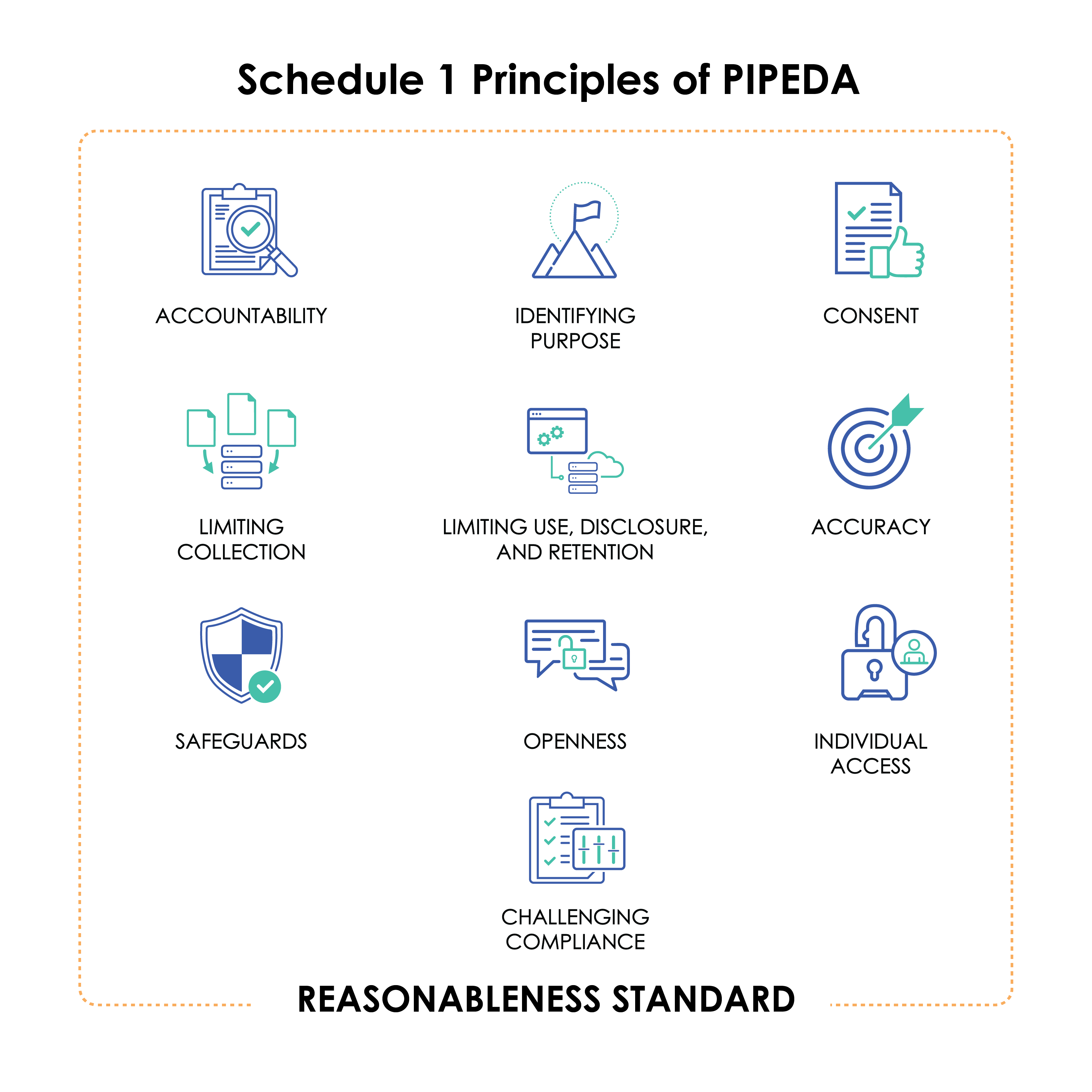

This provision, and Schedule 1, which it cross-references, are the heart of PIPEDA’s substantive rules. As we noted previously in

Module I.E.3, the principles set forth in Schedule 1 are those adopted by the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) as its Model Code for the Protection of Personal Information (“the CSA

Code”).2

These principles are further refined and modified by PIPEDA in Sections 6 through

9.3

a. The Reasonableness Standard

One of the overarching obligations of PIPEDA is that personal information must be handled in a reasonable manner. Subsection 5(3) is the core of this obligation. It states that “[a]n organization may collect, use or disclose personal information only for purposes that a reasonable person would consider are appropriate in the

circumstances.”4

Likewise, in its statement of purpose, PIPEDA attempts to strike a balance between protecting privacy and facilitating the use of personal information by the private sector based upon what “a reasonable person would consider appropriate in the

circumstances.”5

Thus, reasonableness is “the overriding standard set out in

PIPEDA . . .”6

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) has described Subsection 5(3) and its mandate that organizations process data in a reasonable manner as follows:

Subsection 5(3) of PIPEDA is a critical gateway that either allows or prohibits organizations to collect, use and disclose personal information, depending on their purposes for doing so. It is the legal boundary that protects individuals from the inappropriate data practices of companies. It separates those legitimate information management practices that organizations may undertake in compliance with the law, from those areas in which organizations cannot venture, otherwise known as “No-go

zones”.7

This reasonableness standard is applied to the principles set out in Schedule 1. Or put a different way, Subsection 5(3) “is a guiding principle that underpins the interpretation of the various provisions of

PIPEDA.”8

The Federal Court of Appeal, for example, found in the case

Englander v. Telus Communications, Inc., that “even though Part 1 and Schedule 1 of [PIPEDA] purport to protect the right of privacy, they also purport to facilitate the collection, use and disclosure of personal information by the private sector. In interpreting this legislation, the Court must strike a balance between two competing interests. Furthermore, because of its non-legal drafting, Schedule 1 does not lend itself to typical rigorous construction. In these circumstances, flexibility, common sense and pragmatism will best guide the

Court.”9

In other words, it is Subsection 5(3) that helps fill the void between the competing interests at play when processing personal information.

In determining whether data practices are proper, “Subsection 5(3) requires a balancing of interests ‘viewed through the eyes of a reasonable

person.’”10

It is also an “overarching requirement” that is part of, or superimposed upon, all of an organization’s other obligations under

PIPEDA.11

Compliance with this reasonable person standard is, in effect, a necessary baseline for all other practices; it is a necessary but not sufficient condition for complying with PIPEDA and its Schedule 1

provisions.12

For this reason, we will reference the reasonableness standard frequently when discussing PIPEDA’s other substantive provisions in Schedule 1 throughout this study guide.

b. Application of the Reasonableness Standard

In applying the reasonableness analysis to the conduct of organizations processing personal data, an objective view is required. This is a flexible concept. The standard does not strictly look at reasonableness from the perspective of the data controller, nor does it look at it strictly from the subjective perspective of the individual. An analysis must be conducted “in a contextual manner” that looks at all of the surrounding facts related to the collection, use and disclosure of personal

information.13

This “suggests flexibility and variability in accordance with the

circumstances.”14

Factors to be consider might include, for example, the sensitivity of the information, whether there is a legitimate business need, whether processing is effective in meeting that business need, whether less invasive means of achieving the same end are available, and the potential loss of privacy at

issue.15

One court has formulated the analysis as follows: “In considering whether an organization complies with subsection 5(3) of PIPEDA, . . [it should] consider whether (1) the collection, use or disclosure of personal information is directed to a

bona fide business interest, and (2) whether the loss of privacy is proportional to any benefit

gained.”16

It might be helpful to consider some examples of processing activities that have been found to be unreasonable by either OPC or the courts—what the OPC refers to as “no-go zones” of processing. Examples of activities that would be considered unreasonable include: (1) processing that is otherwise unlawful; (2) profiling that leads to unfair, unethical or discriminatory treatment; (3) processing for purposes that are known or likely to cause significant harm to the individual; (4) publishing personal information with the intended purpose of charging individuals for its removal; (5) requiring passwords to social media accounts for the purpose of employee screening; and (6) surveillance by an organization through audio or video functionality of the individual’s own

device.17