- The Council of the European Union (a/k/a “the Council of Ministers” or “the Council”) plays a role similar to that played by Parliament – legislative, budgetary, and political roles

- Composed of one member for each member state and led by a President that rotates every six months

- Must deliberate legislation and vote in public; other actions may be private

- Should not be confused with the European Council (another E.U. institution) or the Council of Europe (a separate international organization)

CIPP/E

0%

Table of Contents

Welcome

I. Introduction to European Data Protection

Section A: Historical Background to E.U. Data Regulation

0/7

1. Introduction

2. Human Rights Laws

a. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

b. The European Convention on Human Rights

3. Early Data Protection Laws and Regulations

a. Early Attempts at a Cohesive Approach

b. OECD Guidelines

c. Convention 108

i. Chapter Two of Convention 108 – Principles of Data Protection

ii. Chapter Three of Convention 108 – Transborder Data Flow

iii. Chapter Four of Convention 108 – Mutual Assistance

d. “Additional Protocol” to Convention 108

e. Convention 108+

4. The Need for a Harmonized European Approach

a. Directives vs. Regulations

b. The Data Protection Directive

c. Charter of Fundamental Rights

5. The Treaty of Lisbon

6. A Modern Framework

a. The General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”)

b. Convention 108+

c. The Law Enforcement Data Protection Directive

d. The ePrivacy Directive

e. Brexit

f. A Timeline of Data Protection in Europe

Section I.A Review

Section B: E.U. Institutions

0/8

1. Introduction

2. European Parliament

a. The Role of the Parliament

i. The Legislative Process

ii. Budgetary Authority

iii. Democratic and Political Authority

b. The Functioning of the Parliament

3. Council of the European Union

a. The Role of the Council

b. The Functioning of the Council

c. Distinction from the Council of Europe

4. European Council

5. European Commission

a. Role in Data Protection

b. Representation and Independence

6. Court of Justice of the European Union

a. The General Court

b. The European Court of Justice

c. Role in Data Protection

7. European Court of Human Rights

a. Jurisdiction of the Court

b. Data Protection Decisions by the Court

Section I.B Review

Section C: E.U. Legislative Framework

0/9

1. Introduction and Revisiting Convention 108

2. The Data Protection Directive

a. Overview

b. Scope

c. Key Principles

d. Article 29 Working Party

3. The ePrivacy Directive

a. Background of the ePrivacy Directive

b. Scope

c. Key Provisions

d. 2009 Amendments – “The Cookie Directive”

e. The “ePrivacy Regulation”

4. The E-Commerce Directive, Digital Services Act, and Digital Markets Act

a. “Information Society Services”

b. Key Principles

c. Relationship to Data Protection

d. The Digital Services Act

d. The Digital Markets Act

5. European Data Retention Regimes

6. The General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”)

a. Background of the GDPR and the LEDP Directive

b. Structure of the GDPR

c. “Opening Clauses”

d. The European Data Protection Board

e. Relationship to Other Legislation

i. References to the Data Protection Directive

ii. The ePrivacy Directive

iii. The E-Commerce Directive

iv. The LEDP Directive

v. Payment Services Directive 2

vi. Data Governance Act

vii. Regulation (EU) 2018/1725

viii. EU Data Act

7. The Law Enforcement Data Protection Directive (“LEDP Directive”)

8. The Network and Information Security Directive (“NIS Directive”) and the NIS 2 Directive

9. The Artificial Intelligence Regulation

Section I.C Review

Knowledge Review #1

II. E.U. Data Protection Law and Regulation

Section A: Data Protection Concepts

0/7

1. Introduction

2. Personal Data

a. “Any Information”

b. “Relating To”

c. “An Identified or Identifiable”

d. “Natural Person”

3. Sensitive Personal Data

a. Special Categories of Personal Data

b. Prohibition on Processing and Exceptions

c. Criminal Convictions and Offenses

4. The Role of Encryption, Anonymization, and Pseudonymization

a. Pseudonymization of Data

b. Anonymous Data

5. Processing

6. Roles in Data Processing

a. Data Subject

b. Data Controller

i. “Natural or Legal Person, Public Authority, Agency or Other Body”

ii. “Determines”

iii. “Alone or Jointly with Others”

iv. “Purposes and Means”

v. “Of the Processing of Personal Data”

c. Data Processor

d. Distinguishing a Controller from a Processor

Section II.A Review

Section B: Territorial and Material Scope of the GDPR

0/5

1. Introduction

2. Territorial Scope (Establishment in the E.U.)

a. How to Determine “Establishment”

b. How to Determine if “the Context of the Activities” is in the Establishment

c. Application to Data Processors

3. Territorial Scope (Non-Establishment in the E.U.)

a. Data Subjects in the Union

b. Targeting Criteria

i. Offering of Goods and Services

ii. Monitoring Behavior

c. Application to Data Processors

d. Application Due to Public International Law

4. Material Scope of the GDPR

a. National Security Exceptions

b. Household Activities

c. Prevention, Investigation, Detection, and Prosecution of Criminal Offenses

d. Processing by E.U. Institutions

Section II.B Review

Section C: Data Processing Principles

0/8

1. Introduction

2. Lawfulness, Fairness, and Transparency

a. Lawfulness

b. Fairness

c. Transparency

3. Purpose Limitation

4. Data Minimization (Proportionality)

5. Accuracy

6. Storage Limitation

7. Integrity and Confidentiality

Section II.C Review

Section D: Lawful Processing Criteria

0/8

1. Introduction

2. Consent

a. The Elements of Consent

i. Freely Given

ii. Specific to the Processing

iii. Informed

iv. Unambiguous

b. Demonstrating Consent

c. Consent and Alternative Legal Bases

d. Obtaining Consent from Children

3. Contractual Necessity

4. Legal Obligations, Vital Interests, and Public Interest

a. Legal Obligations

b. Protecting Vital Interests

c. Public Interest

5. Legitimate Interests

a. What is a “Legitimate Interest”?

b. What are the Interests and Fundamental Rights of Data Subjects?

c. The Balancing Test

6. Special Categories of Processing

a. Sensitive Data Types

b. Prohibition and Derogations

7. Processing That Does Not Require Identification

Section II.D Review

Knowledge Review #2

Section E: Information Provision Obligations

0/6

1. Transparency Principle

2. When Information is Collected from the Data Subject

3. Information Collected from Third Parties

a. Timing of Information Provision

b. When Disclosures are Not Necessary

i. When Data Subject Already Has the Information

ii. Impossibility or Disproportionate Effort

iii. Obtaining or Disclosing is Laid Down by Law

iv. Confidentiality by Virtue of a Secrecy Obligation

4. Disclosure Requirements Under the ePrivacy Directive

5. Privacy Notices

a. Designing an Effective Privacy Notice

i. Common Elements

ii. Accounting for Children

iii. Layered Notices

iv. Just-in-Time Notices

v. Privacy Dashboards

vi. Privacy Icons and Visualization Tools

vii. One or Multiple Privacy Notices?

b. Updating a Privacy Notice

Section II.E Review

Section F: Data Subject Rights

0/10

1. Introduction

2. Right to Access Information

a. Purpose and Structure of the Right to Access

b. Responding to Data Subject Access Requests (DSARs)

i. Determining What Information Relates to the Requesting Data Subject

ii. The Modalities of a Response

3. Right to Rectification

4. Right to Erasure (“Right to be Forgotten”)

a. Search Engines and the Right to be Forgotten

5. Right to Restrict Processing

6. Right to Data Portability

7. Right to Object to Processing

8. Right to Not Be Subject to Automated Decision-Making and Profiling

9. Restrictions on Data Subject Rights

a. When Are Restrictions Permitted?

b. Additional Requirements

Section II.F Review

Section G: Security of Personal Data

0/6

1. Technical and Organizational Security Measures

a. The CIA Triad

b. Security Controls and Protection Mechanisms

i. Purpose of Controls: Preventative, Detective, and Corrective

ii. Types of Controls: Physical, Administrative, and Technical

c. Security Controls Under Article 32

d. ISO Standards 27001 and 27002

e. Managing Employees

2. Privacy Incidents: Planning, Detection, and Response

a. Response Planning

i. Developing a Plan

ii. Training

iii. Key Roles and Responsibilities

iv. Insurance Coverage

v. Managing Vendors

b. Incident Detection

c. Incident Response

d. Incident Follow-Up

3. Breach Notification

a. What is a “Personal Data Breach”

b. Notifying Regulators (Article 33)

i. When is Notification Required?

ii. What Must be Included in a Notice to a DPA?

iii. Notification by Processors

c. Notifying Data Subjects

i. When is Notification Required?

ii. What Must be Included in a Notice to Data Subjects?

d. Ransomware Breach Notification

4. Vendor Management and Data Sharing

a. Choosing a Third-Party Data Vendor

b. Data Sharing Agreements

5. Cybersecurity and the NIS 2 Directive

a. CSIRTs and NIS Cooperation Group

b. Operators of Essential Services and Digital Service Providers

Section II.G Review

Knowledge Review #3

Section H: Accountability Requirements

0/8

1. Introduction to the Accountability Principle

a. Accountability Generally

b. Accountability Under the GDPR

2. Responsibilities of Controllers and Processors

a. Organizational Privacy Policies

b. The Privacy Policy Life Cycle

c. Key Components of a Privacy Policy

d. Implementing a Privacy Policy

e. Responsibilities of Joint Controllers and Article 26

3. Data Protection by Design and by Default

a. The Seven Principles of PbD

b. Data Protection by Design and Default Under the GDPR

i. Scope

ii. Article 25(1) – Data Protection by Design

iii. Article 25(2) – Data Protection by Default

c. ISO Privacy by Design Standards

4. Documentation and Cooperation with Regulators

a. Records of Processing Activities

b. Article 31 – Cooperation with DPAs

5. Data Protection Impact Assessment

a. Privacy Impact Assessments

b. Data Protection Impact Assessments

i. When is a DPIA Required?

ii. What Must Be Included in a DPIA?

iii. Consultation with Supervisory Authorities

6. Data Protection Officers

a. When is Appointment of a DPO Required?

b. The Role of a DPO

7. Auditing a Privacy Program

a. Types of Audits

b. The Audit Life Cycle

c. Attestations and Self-Assessments

Section II.H Review

Section I: International Data Transfers

0/8

1. Introduction

a. The Risks of International Data Transfers

b. The Surprise Minimization Rule

c. The Framework for Data Transfers to Third Countries Under the GDPR

d. What Constitutes a “Transfer”?

2. Adequacy Decisions

a. The Making of an Adequacy Decision

b. Adequacy Decisions and the United States

3. Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs)

a. Approval by a Supervisory Authority

b. What Must be Included in BCRs

4. Standard Contract Clauses

a. Schrems II and the Use of SCCs

b. New Standard Contract Clauses (2021)

c. Ad Hoc Contract Clauses

d. U.K. Standard Contract Clauses

5. Codes of Conduct and Certifications

a. Codes of Conduct

i. What Should be Included in a Code Intended for Transfer?

ii. The Adoption Process

b. Certification Mechanisms

6. Derogations

7. Transfer Impact Assessments

Section II.I Review

Section J: Supervision and Enforcement

0/10

1. Introduction

2. National Supervisory Authorities and Their Powers

a. DPA Tasks

b. DPA Powers

i. Investigatory Powers

ii. Corrective Powers

iii. Advisory Powers

c. Activity Reports

d. Prior Consultation Under Article 34(4)

e. Competence of Supervisory Authorities

i. Who is the Lead Supervisory Authority?

ii. When May a Non-Lead Supervisory Authority Act?

3. Cooperation Between Supervisory Authorities

a. Cooperation Procedure Under Article 60

i. When Does it Apply?

ii. What Supervisory Authorities are “Concerned”?

iii. Mutual Obligation to Cooperate

iv. Information Sharing

v. Draft Decisions

b. Mutual Assistance

c. Joint Operations

d. Regulatory Rivalries

e. Amicable Settlements

4. The European Data Protection Board

a. Structure of the EDPB

b. Tasks of the EDPB

c. Consistency Mechanism

i. Consistency Opinions

ii. Dispute Resolution

iii. Urgency Procedure

5. European Data Protection Supervisor

a. Independence and Secrecy

b. Tasks and Powers

6. Self-Regulation Under the GDPR

7. Regulation by Data Subjects

8. Infringements and Fines

a. Article 83(4)

b. Article 83(5)

c. Factors to Consider in Establishing a Fine

d. One or Multiple Sanctionable Conduct(s)?

e. Major Fines

f. Additional Member State Penalties

g. What Constitutes an Undertaking for Article 83?

9. Liability to Data Subjects

a. Representative Actions

b. Collective Redress Directive

c. Data Subject Compensation

Section II.J Review

Knowledge Review #4

III. Compliance with the GDPR

Introduction

Section A: Employment Relationships

0/9

1. Introduction

2. Legal Basis for Processing of Employee Data

a. Legal Basis for Processing

i. Consent of the Employee

ii. Necessary to Fulfill an Employment Contract

iii. Necessary to Comply with a Legal Obligation

iv. Necessary for the Employer’s Legitimate Interests

b. Special Categories of Employee Data

3. Storage of Personnel Records

4. Workplace Monitoring

a. Background Checks

b. Monitoring the Workplace

i. Necessity

ii. Transparency and Notice

iii. Legitimacy

iv. Proportionality

5. E.U. Work Councils

6. Whistleblowing Systems

a. Whistleblowing Policies

b. Sarbanes-Oxley Act

7. Bring Your Own Device (“BYOD”) Programs

8. Risks Involved in Processing Employee Data

Section III.A Review

Section B: Surveillance Activities

0/6

1. The Conflict Between Surveillance and Privacy

2. Interception of Communications

3. Video Surveillance

a. The Household Use Exception

b. Lawfulness of Processing

i. Consent of the Data Subject

ii. Legitimate Interests

iii. Necessary for the Public Interest

c. Conducting a DPIA

d. Video Surveillance as Biometric Data

e. Data Subject Rights

i. Right to Transparency

ii. Right to Access

4. Geolocation Data

a. Types of Location Tracking

i. GPS Tracking

ii. Wi-Fi, Cell Tower, and Bluetooth Tracking

iii. RFID Chips

iv. Other Sources of Location Data

v. IP Address

b. Location-Based Services

5. Biometric Data

a. Biometric Data Under the GDPR

b. Use of Facial Recognition by Law Enforcement

i. Lawful Basis

ii. Automated Processing and Profiling

iii. Data Subject Rights

iv. Other Considerations

Section III.B Review

Section C: Direct Marketing

0/6

1. Overview of Direct Marketing

a. WP29 Guidance on What Constitutes Direct Marketing

b. Digital vs. Non-Digital Direct Marketing

c. Direct Marketing Under the GDPR

i. Direct Marketing as a Legitimate Interest

ii. The Right to Opt-Out

d. Direct Marketing Under the ePrivacy Directive

e. Robinson Lists

2. Telemarketing

a. Person-to-Person vs. Automated Calls

b. Business-to-Business vs. Business-to-Consumer Calls

3. Email Marketing

a. “Electronic Mail” Defined

b. Consent Requirements

c. Restrictions and Information Provision Obligations

d. B2B vs. B2C Email Messages

4. Other Types of Direct Marketing

a. Postal Mail Marketing

b. Fax Marketing

c. Location-Based Marketing

5. Behavioral Advertising

a. Tracking Consumers Across the Internet

i. Cross-Device Tracking

ii. Examples of Other Methods

iii. Creating Consumer Profiles

b. Parties Involved in Behavioral Advertising

c. Legal Framework

i. Application of the GDPR

ii. Application of the ePrivacy Directive

d. Compliance Challenges

i. Who is the Data Controller?

ii. Providing Processing Information

iii. Legal Basis for Processing

iv. Special Categories of Data

Section III.C Review

Section D: Internet Technologies and Communications

0/6

1. Cloud Computing

a. Controllers and Processors in Cloud Computing

b. Cloud Computing Contracts

c. E.U. Cloud Code of Conduct

2. Web Cookies and Similar Technologies

a. Web Cookies

i. Types of Web Cookies

ii. Cookies as Personal Data

iii. Who is the Controller?

iv. Consent Requirements

v. The Planet49 Decision

vi. Recent Changes to the Browser

vii. Cookie Banner Transparency

b. IP Addresses and the Internet “Phonebook”

c. IP Address as Personal Data

3. Social Media Targeting

a. Who is the Data Controller?

b. Types of Data Used to Target

c. Compliance Challenges

i. Data Subjects and Personal Data

ii. Transparency Requirements

iii. Right of Access

iv. Special Categories of Data

v. Personal Data of Others

vi. Children’s Data

d. Dark Patterns in Social Media Platforms

4. Search Engine Targeting

a. Data Controllers

b. Compliance Challenges

i. Data Retention

ii. Further Processing

iii. Data Subject Rights

5. Artificial Intelligence

a. Application of the GDPR

b. E.U. Artificial Intelligence Regulation

i. Scope of the AI Act: AI Systems, Providers, Deployers, and Extraterritorial Reach

ii. Categorization of Risk

iii. Accountability and Transparency Requirements

iv. General-Purpose AI Models

v. Enforcement and the European Artificial Intelligence Board

6. Other Frontier Technologies: Internet of Things (IoT), Big Data, Blockchains, and Data Ethics

a. Internet of Things (IoT)

i. Who is the Controller?

ii. Transparency and the Problem of Obtaining Consent

iii. Security

iv. EU Data Act

b. Big Data

c. Blockchains and Cryptocurrencies

d. Data Ethics

i. What is Data Ethics?

ii. Specific Examples of Ethical Principles

Section III.D Review

Knowledge Review #5

Conclusion

Full Exam #1

Full Exam #2

Council of the European Union

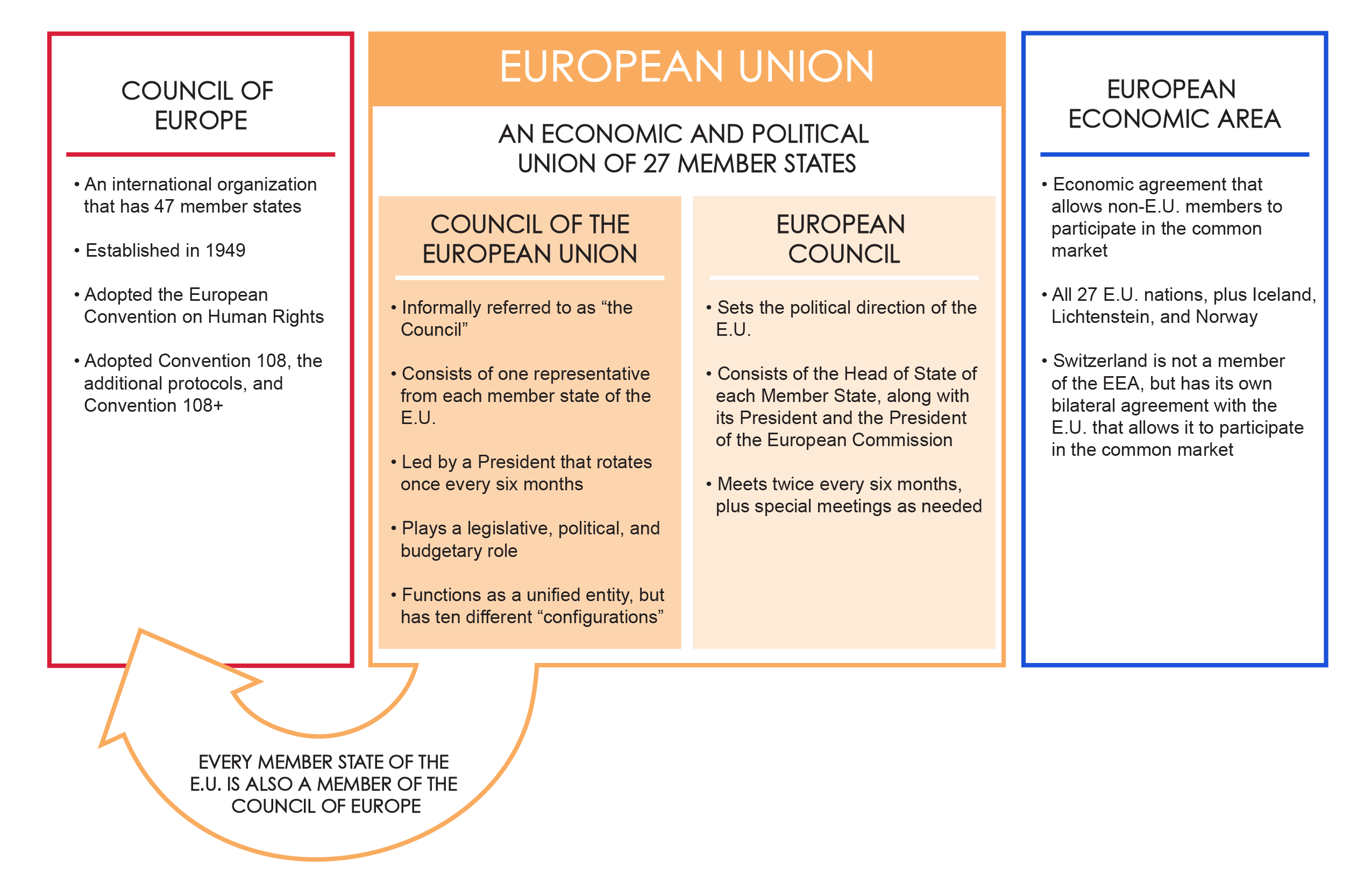

The Council of the European Union—sometimes informally referred to as the “Council of Ministers,” or more simply, the “Council”—is the oldest of all E.U. governing institutions. Its genesis can be traced to the early treaties establishing a common European market. The Council of the European Union should not be confused with the European Council, a separate E.U. institution discussed in the next Module. Nor should it be confused with the Council of Europe, a distinction we discuss further below. When reference is made simply to the “Council,” this is a reference to the Council of the European Union—not the European Council or the Council of Europe.

The Council is comprised of one representative from each member state of the European Union.1 This representative is intended to speak on behalf of the nation it represents, and it may cast its vote on behalf of that nation.2 The representative, therefore, is ultimately accountable to the citizens of the member state that it represents, along with that member state’s national parliament.

The Council is led by a President, a position that rotates among member states every six months on an equal basis.3 The role of the President is to preside over meetings of the Council, set its agenda, and represent the Council in its relationship with the European Commission and Parliament.4

a. The Role of the Council

Under the modern E.U. framework, the Council plays a legislative, political, and budgetary role—similar to the European Parliament. Article 16(1) of the Treaty on European Union, as amended, provides: “The Council shall, jointly with the European Parliament, exercise legislative and budgetary functions. It shall carry out policy-making and coordinating functions as laid down in the Treaties” governing the E.U.5

As discussed in the preceding Module, there are three primary procedures used to enact legislation in the E.U. In the ordinary procedure, both the Council and Parliament must agree on legislation. In the consultative procedure, the Council has sole authority to enact legislation, though it must consult the Parliament in a non-binding process. In either procedure, the Council has authority to amend proposed legislation before its adoption. As noted previously, data protection legislation must be adopted according to the ordinary legislative procedure. Therefore, the Council plays a roughly equal role with the Parliament in the development of such legislation.

When the Council meets to deliberate and vote on draft legislation, it must conduct such meetings in public.6 The text of the Treaty on European Union is silent on whether the Council’s meetings must be open to the public when it meets for purposes other than exercising its legislative functions. Presumably, therefore, such meetings can be held in private.

b. The Functioning of the Council

The voting procedure within the Council is governed by the treaties establishing the E.U. In some cases, members are permitted only one vote each. But, in other instances, members are permitted several votes based upon the percentage of the E.U. population that the member represents.

Acts by the Council can include both regulations and directives. Additionally, however, the acts of the Council can take the form of decisions, common actions, common positions, recommendations, opinions, conclusions, declarations, or resolutions. The treaties establish whether a simple majority, qualified majority, or unanimous consent are necessary to take any of these listed actions.

The Council is intended to function as a unified entity. When the Council meets, however, it does not necessarily meet as a collective group. Rather, the Treaty on European Union calls for the Council to “meet in different configurations.”7 There are currently ten different configurations, which include: (1) Agriculture and Fisheries; (2) Competitiveness; (3) Economic and Financial Affairs; (4) Education, Youth, Culture, and Sport; (5) Employment, Social Policy, Health and Consumer Affairs; (6) Environment; (7) Foreign Affairs; (8) General Affairs; (9) Justice and Home Affairs; and (10) Transport, Telecommunications and Energy.8

c. Distinction from the Council of Europe

As noted above, the Council of the European Union should not be confused with the European Council, another E.U. institution. It is equally as important, however, not to confuse the Council of the European Union with the Council of Europe.

The Council of Europe was first established in 1949 as a consultative body.9 Unlike the Council of the European Union and the European Council, the Council of Europe is not an institution of the E.U. Rather, the Council of Europe is an international organization of 47 member states that is entirely separate from the E.U. In its early years, it produced the European Convention on Human Rights.10 “[T]he aim of the Council of Europe is to achieve a greater unity between its Members for the purpose of safeguarding and realizing the ideals and principles which are their common heritage, and facilitating their economic and social progress.”11

In contrast, the European Union is a political and economic union of 27 member states (following the exit of the United Kingdom). Every member of the European Union is also a member of the Council of Europe. Being a part of the Council of Europe, however, is not a prerequisite for inclusion into the European Union.

Explanatory Note: Another distinction to be aware of is that between the E.U. and the European Economic Area (“EEA”). The EEA consists of all E.U. member states, along with non-member states of Iceland, Lichtenstein, and Norway. The EEA is based on a 1994 agreement, which allows these non-member states to participate fully in the E.U.’s internal market. Switzerland is not a member of the EEA, but it has a set of bilateral agreements with the E.U. that also permits it to take part in Europe’s internal market.

Key Points

Sources

1. Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union art. 16(2), June 7, 2016, 2016 O.J. (C 202) 1, 15.

2. Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union art. 16(2), June 7, 2016, 2016 O.J. (C 202) 1, 15.

3. Council of the European Union, The Presidency of the Council of the EU: A Rotating Presidency, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/council-eu/presidency-council-eu/.

4. Council of the European Union, The Presidency of the Council of the EU: A Rotating Presidency, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/council-eu/presidency-council-eu/.

5. Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union art. 16(1), June 7, 2016, 2016 O.J. (C 202) 1, 15.

6. Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union art. 16(8), June 7, 2016, 2016 O.J. (C 202) 1, 15.

7. Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union art. 16(6), June 7, 2016, 2016 O.J. (C 202) 1, 15.

8. Council of the European Union, Council Configurations, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/council-eu/configurations/.

9. Council of Europe, Founding Fathers, https://www.coe.int/en/web/about-us/founding-fathers.

10. Council of Europe, The Council of Europe at a Glance, https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/the-council-of-europe-at-a-glance.

11. Council of Europe, Statute on the Council of Europe, Art. 1(a), https://rm.coe.int/1680306052.