As you will recall from

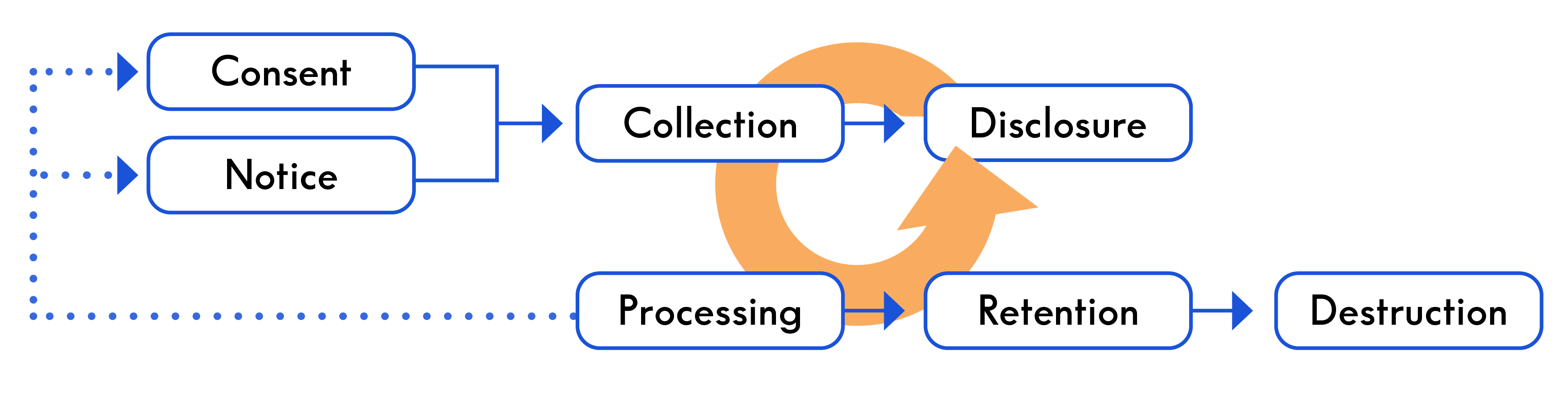

Module I.A.2, the processing of personal data refers to nearly anything that can be done with data, including collection, use, and destruction of that data. When it comes to appropriately protecting the privacy interests of individuals, adequate steps must be taken to protect data processing in all its forms. One of the core principles of Privacy by Design (“PbD”) is end-to-end security, from before data is processed until data is

destroyed.1

It is helpful, therefore, to think of personal data as existing across a life cycle.

The Data Life Cycle typically refers to the following six steps: (1) collection; (2) processing; (3) use; (4) disclosure; (5) retention; and (6)

destruction.2

Other iterations, refer to collection, use, access, sharing, transfer, and destroying data. According to the IAPP, this life cycle “recognizes that data has different values, and requires [different] approaches, as it moves through an organization from collection to

deletion.”3

The above diagram is general in nature and adaptable to different scenarios. While similarities will exist across all organizations, the specific data life cycle for the personal data processed by your organization will have unique nuances based upon the business and privacy objectives of your organization.

a. Data Life Cycle Management

Each stage of the data life cycle presents unique risks and challenges for organizations processing personal data. Organizations must therefore be mindful of the privacy implications of that processing at each stage of the data life cycle. This is a concept referred to as

Data Life Cycle Governance or

Data Life Cycle Management, which the IAPP defines as follows:

Also known as Information Life Cycle Management (ILM) or data governance, DLM is a policy-based approach to managing the flow of information through a life cycle from creation to final disposition. DLM provides a holistic approach to the processes, roles, controls and measures necessary to organize and maintain data and has 11 elements: Enterprise objectives; minimalism; simplicity of procedure and effective training; adequacy of infrastructure; information security; authenticity and accuracy of one’s own records; retrievability; distribution controls; auditability; consistency of policies; and

enforcement.4

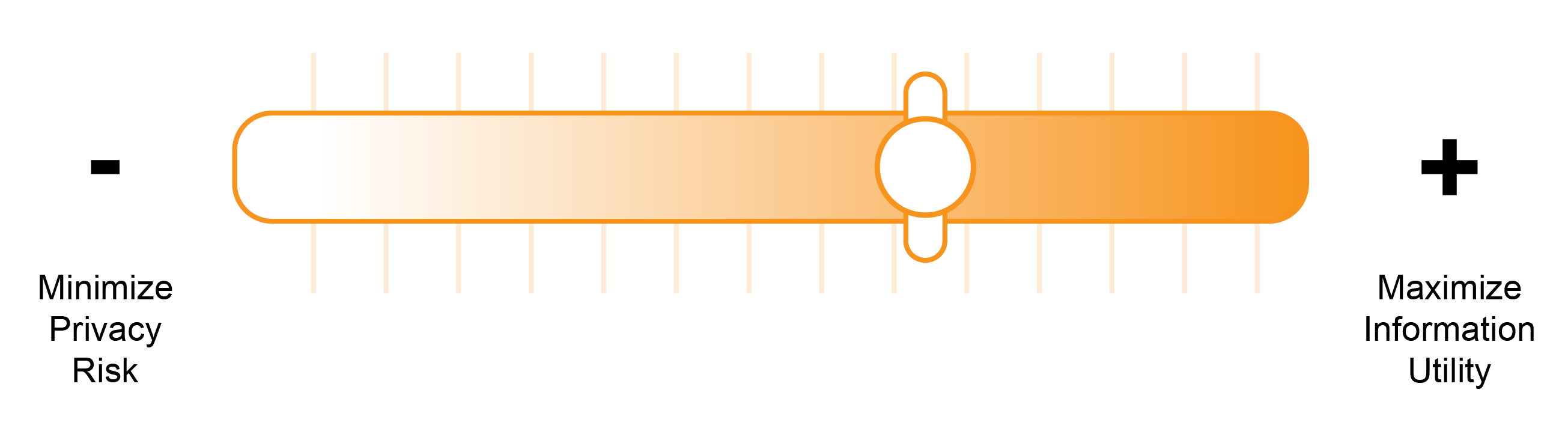

The above eleven elements all require a delicate balance, and each is likely to involve tradeoffs. Simplification of a DLM policy may, for example, result in some unnecessary information being retained. Making data easily retrievable, on the other hand, may increase the security risks to the data being retrieved.

An organization’s privacy objectives and business needs will typically determine how it approaches DLM. While not always in direct conflict, the more liberally personal data is used by an organization for business purposes, the more likely it is that the privacy risks associated with using that data will increase. It can be helpful to think of this as a spectrum—at one end is the

<>maximize-information-utility objective and at the other extreme is the

<>minimize-privacy-risk

objective.5

How these objectives are balanced against one another will be unique to an organization and dictate many internal policies regarding the handling of personal data.

b. The Role of Notice and Consent in Data Processing

As you will observe in the Data Life Cycle chart above, notice and consent play an important role in data governance. Some combination of notice and consent will typically dictate the extent to which an organization may process personal data. Under the General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”), for example, a data controller is prohibited from processing personal data, unless it has a lawful

purpose.6

One lawful basis to process personal data is

consent.7

Consent may be express or implied, with certain types of data collection requiring express approval. Express, affirmative consent is sometimes referred to as “Opt-in” consent and requires an affirmative indication or act that provides consent to collect or use a person’s information. The counterpart to this, “Opt-out” consent, is a passive form of acceptance that is implied by a person’s conduct or actions, as well as the context of the transaction. The distinction between opt-in and opt-out consent is often an important concept to be aware of when reviewing applicable laws and regulations; some laws specifically require that a form of opt-in consent be obtained from a consumer before collecting or processing personal information, while other laws permit opt-out consent.

Obtaining consumer consent may not be appropriate in every situation. The “No Option” form of consumer choice involves situations in which the authority to collect and utilize data is implied from the situation. One example of when this might be appropriate is with respect to product fulfillment. The authority to share these pieces of information with these third parties is implied from the nature of the transaction itself, and specific consent from the consumer to process information in this manner is therefore not necessary.

Notice is often provided through an external privacy notice. Notice is closely correlated with consent. Without providing a data subject with adequate notice of how his or her personal data will be processed, obtaining informed, express consent would be

impossible.8

In this respect, notice of processing activities often sets the outer bound of how data may be processed—including what data is collected, how it is used, to whom it is disclosed, and the extent to which it is retained. It would not be proper to repurpose data—i.e., use it for a purpose other than for which it was originally collected. Putting data to a secondary use without the user’s consent risks creating privacy harms, as well as opening up the data controller to potential legal liability.

c. Data Collection

Data is collected in the modern data environment in a number of unique ways. These include the following:

-

First Party Collection – First party collection is when a “data subject provides personal data to the collector directly, through a form or survey that is sent to the collector upon the data subject submitting the

information.”9

-

Third Party Collection – Third party collection is when “[d]ata [is] acquired from a source other than directly from the subject of the

data.”10

-

Surveillance – Surveillance refers to “[t]he observation and/or capturing of an individual’s activities,” with or without their

knowledge.11

In addition to the above, Repurposing is the process of “[t]aking information collected for one purpose and using it for another purpose later

on.”12

This may also, in some sense, be considered a form of data collection; it is “collected” for purposes of a secondary use.

Some personal data is collected automatically, often without the user’s knowledge. This automatic collection of user data is commonly referred to as

Passive Data Collection.13

Passive data collection can take many forms. Online it is commonly done through the use of cookies and the identification of specific

devices.14

For example, web server logs often will record information regarding a website visitor’s IP address and the type of browser the visitor is using, among other information. All of this data is collected automatically, and often without express consent.

Personal information can also be collected with a data subject’s knowledge, which is referred to as

Active Data Collection.15

This can be done, for example, through the use of web forms—i.e., a part of a webpage that allows users to input data in a text field, dropdown menu, radio buttons, or other means and then “submit” that information to a web server to process information or store that information in a

database.16

d. Data Retention and Destruction Policies

DLM covers the processing of data from cradle to grave—i.e., from initial collection through the destruction of data. Accordingly, an organization’s data retention and data destruction policies play a vital role in DLM for any organization. The destruction and retention policies adopted by an organization should be guided by the principle that data should be retained only for so long as necessary to achieve its purpose. This is determined based upon the business goals of the organization, along with laws, regulations, and industry standards. After data is no longer necessary for the purpose for which it was originally retained, the data should be appropriately destroyed or anonymized. These practices should be adequately documented and consistently followed throughout the organization.

Adequate data retention policies are a key part of the accountability principle. Organizations must be aware of the need to address potential data loss. More sensitive data should be stored in a more secure fashion, including with the use of encryption.

Retaining information unnecessarily creates privacy risks. At the same time, destroying data prematurely also risks legal complications and privacy harms. It is therefore important to adequately document practices and ensure that they are consistently followed throughout the organization. This destruction plan should set out when and how data should be destroyed in detail.

Data destruction is one of the most powerful ways of protecting personal data. After all, data cannot be improperly accessed if it no longer is in existence. Electronic data can be destroyed by overwriting or the process of

degaussing.17

Shredding, melting, and burning are common means of destroying data held in physical

form.18

Policies regarding the destruction of data should be specific and detailed to ensure proper destruction based on the type of data at issue or the manner in which it is held. It should cover data in all its forms, including back up data and cached

data.19

A key part of protecting the physical environment of an organization’s data is appropriate media sanitization. Digital data might exist on physical objects, such as a flash drive or computer hard drive. Proper destruction requires a media sanitization strategy. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication 800-88 Rev. 1 sets forth appropriate guidelines for organizations to follow with respect to sanitizing

media.20

Under these guidelines, media may be sanitized in one of three ways—clearing, purging, or destroying the

data.21

The data retention and data destruction practices of an organization may be dictated by applicable law. In Europe, the “right to be forgotten” under Article 17 of the General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) requires data controllers to erase information concerning a data subject upon request, with only a few limited

exceptions.22

There are also data destruction requirements contained in various laws throughout the United States, such as the Fair Credit Report Act (as amended by the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act of

2003).23

The timing of data destruction is typically an important component of applicable data destruction laws. Timing may be based on specific length of time (e.g., 45 days) or on more ambiguous standards, such as when the data is no longer necessary for the purpose for which it was originally retained.

On the other hand, applicable law may also require that data be retained for a specific length of time. Retention may be necessary in other instances as well, such as when the organization is involved in litigation or the subject of a governmental investigation.

Legal requirements aside, developing a data retention and destruction policy starts with collecting information about what data is maintained and how it is used. Some questions are particularly important to answer in developing data retention and destruction policies, including: Why was the information originally collected? Why is the organization retaining it? And how long does the information remain useful to the organization? An analysis of the eleven elements in the DLM model is likely to answer these questions. As part of this process, stakeholders across the organization should be brought into the process to ensure legal compliance and that business objectives are satisfied.